INTERVIEW | JONATHAN LABEZ @JMLABEZ

FEATURED PORTRAIT | SCOTT OLSEN

SKATE PHOTOS | GREG SCHLOSSER @YOUNGEREGG

Blade culture (like skateboard culture) has a problem with substance abuse. We end sessions and celebrate events with beer and blunts, which normalizes it. As a collective, there is a tendency of seeing younger skaters as more mature, erroneously equating a person’s talent on skates to mean experienced at life. In part because older skaters with more life experience have a tendency of indoctrinating younger skaters to things they might not experience otherwise.

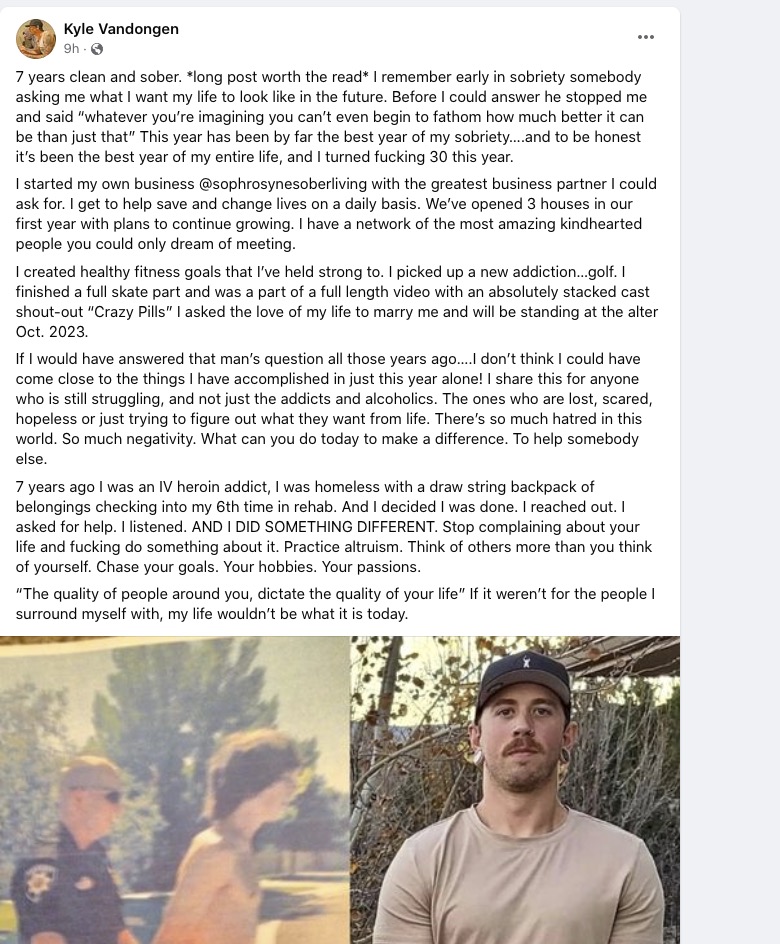

I approached Kyle Vandongen about discussing his history with substance abuse after catching his Facebook post earlier in the year on his sobriety of 7 years and what he has done to not only better his life but the lives of others as the owner of Sophrosyne Sober Living. In a moment of public vulnerability, Kyle wrote about having been a IV heroin addict without a place to live, hardly anything to his name except a drawstring backpack with all his worldly possessions, checked into rehab for a sixth time. It was that nexus point Kyle would choose to change and seek help. From his former destitute life, Kyle was able to not only rebuild, but flourish and find compassion for others like himself who are struggling. In his own words, Kyle said:

“I share this for anyone who is still struggling, and not just the addicts and alcoholics. The ones who are lost, scared, hopeless or just trying to figure out what they want from life. There’s so much hatred in this world. So much negativity. What can you do today to make a difference. To help somebody else.”

As the brother of someone with long-standing substance abuse, I worry daily and keep preparing myself for the worst. To be the family member, friend, or partner of someone with an addiction, nothing causes deeper pangs than knowing there’s nothing you can do to change their behavior, only they can make that decision for themselves.

In this interview with Kyle, it’s my hope that those struggling will read his story and decide today is the day they change their lives for the better.

What are your earliest experiences with substance abuse in blade culture?

As far as the guys I grew up skating with, I was definitely on the younger side of the group (by around four or five years.) The first time I drank and smoked was at 15 with all the dudes I skated with. They had been partying for years before that, which I had never been a part of. After that first drink, it became more of a regular thing: drinking and smoking on the weekends were just part of the routine.

We would skate during the day and drink and party at night. It made me feel more included in the community and gave me a sense of maturity, feeling older than I actually was (since I was just a freshman in high school.)

Meanwhile, I didn’t recognize any of it as “substance abuse.” To me, it was just partying and having a good time. In hindsight, I see that drinking gave me a feeling of confidence and inclusion I hadn’t previously felt. It would be an early warning sign of what was to come.

How did those early experiences sit with you at the time? How do you feel about them now?

At the time, those experiences were fun, care-free, and overall, a good time. We were young with little to no responsibilities. I never thought of any of it as a negative thing. Even nowadays, I don’t necessarily think about most of those times as negative. Those were [my] formative years; we need to experience good and bad in order to learn and grow.

That said, I do recognize the alcohol abuse was very heavy. We referred to ourselves as “team blackout.” That was probably a major red flag.

When did you feel you went from recreational use to full on addiction? What drugs did you find yourself gravitating towards?

Hindsight is always 20/20. I believe from day one, I was an addict.

I now recognize I drank for more than effect. I drank because it finally made me feel comfortable in my

own skin. In the early years, it was just alcohol and weed. I recognize cannabis is beneficial for a lot of people, but for myself I not only abused it, but I relied on it. I couldn’t do anything without rolling a joint before school, skating, social activities, even sitting at home alone playing video games. It made everything more enjoyable to me and released a lot of anxiety I struggled with.

I lived down the street from my high school and could walk there within 5 minutes. A lot of times during lunch I would go home and drink alone, then go back to school. I didn’t have the proper coping mechanisms at that time to deal with the way I felt on the inside. I used substances to mask those feelings.

I dabbled with a bit of everything in those early years— alcohol, weed, psychedelics, adderall, cocaine, and painkillers. In later years, heroin, crack, and benzos [Benzodiazepines]. Heroin and benzos would become my drugs of choice.

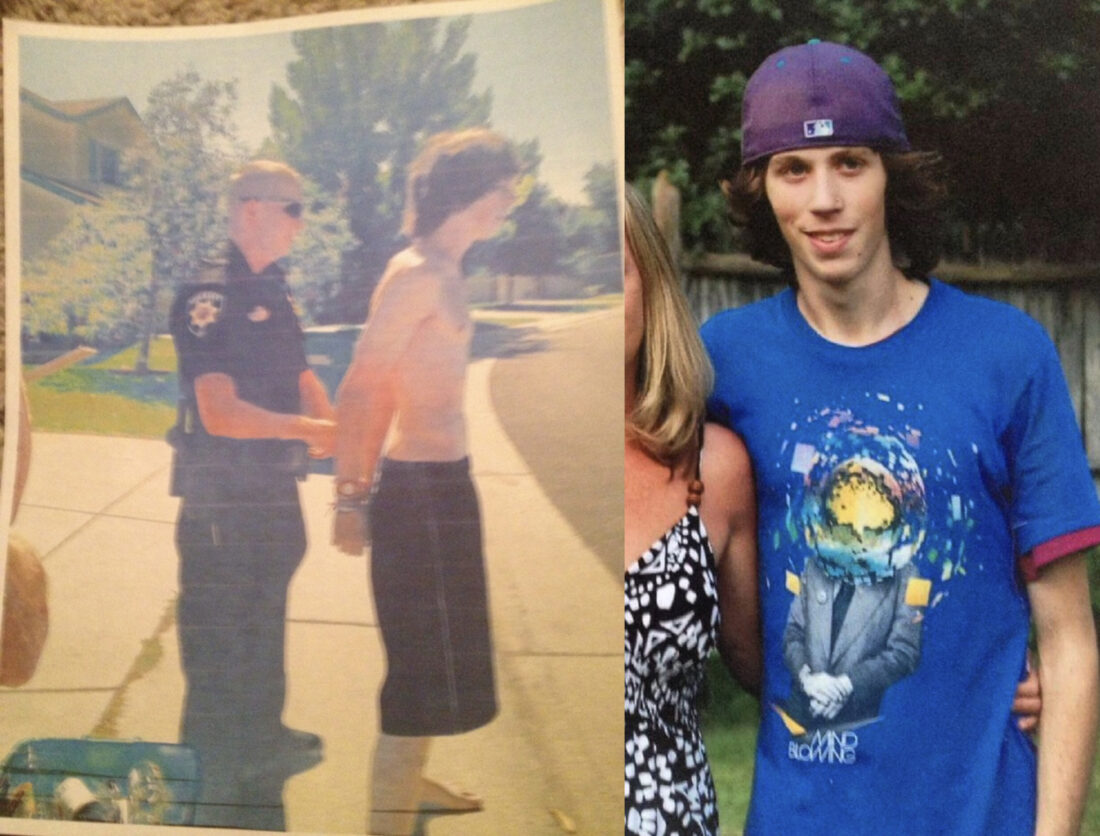

In our phone conversation, you shared the story of having walked in the snow, completely drunk, having walked to your parent’s home which was nowhere near yours. The police found you in a neighbor’s lawn, not in a cognizant state. Three of your fingers had severe frostbite damage and needed amputation a week later.

What was going on at this point in your life?

This was a major turning point in my life but unfortunately it wasn’t a learning experience to get my shit together. It got much worse from there.

I was 19 years old and enrolled at Western State University, a mountain college near Crested Butte, Colorado (also known as ‘Wasted State’), when my alcoholism took off. Drinking was no longer just a weekend activity but a daily necessity. I didn’t go to class. I would drink all day and snowboard.

That New Year’s Eve I went back to my hometown of Highlands Ranch, Colorado to party with my friends for the holiday. I drank to a blackout state which wasn’t out of the ordinary for me. I was at a house party that had been broken up by the cops and everyone scattered. I was a few miles from my parent’s house and proceeded to stumble all the way home in the snow. It was in the negative degrees outside. Stumbling and getting back up repeatedly on that walk, I made it to my best friend’s house which was two doors down from my parent’s home. An off-duty police officer who happened to drive by saw me standing on their driveway, just swaying back and forth. He pulled over, yelled over to me. Apparently, I just dove into the ground (which I have no recollection of.)

Next thing I know, I woke up in the hospital with severe frostbite on both hands, feet, and knees. All of my fingers were fucked! I lost three fingers on my left hand, which all things considered was an absolute godsend. Another hour out in the snow and I would not be here.

With losing fingers though, I gained an almost unlimited supply of painkillers, which were abused right off the bat. Shortly after, heroin became my go-to drug.

I had lost fingers…didn’t get sober. I had been homeless… didn’t get sober. I had OD’d… didn’t get sober. Yet here I was with a stable job, roof over my head, no significant event taking place, and I had this moment of clarity.

Having been and out of rehab 6 times, lived in multiple sobriety homes, and now the co-owner of several sobriety homes under the name Sophrosyne Sober Living, what are some of the reasons people have trouble getting sober?

Right | Kyle with his partner opening their first sober living home

This is a question I get asked frequently and it’s a very complicated question with a very simple answer that is completely dependent on the individual. It’s really just the willingness to make a change and do whatever it takes to do so.

There are a lot of variables that come into play. Some people on’t have insurance or the financial means to go to a nice rehab facility. Some don’t have the family support or love and care to help them. At the end of the day there are ALWAYS resources for those who need help and are willing to do whatever they need to do to change.

The first few times I went into treatment, I was forced/pushed to go. I wasn’t doing it for myself, I was doing it to appease others. It needs to be a personal choice rooted in the belief that you can change, you can break the cycle, you can ask for help. There are those out there to help you down that journey. You do not have to do it alone.

Being a male-dominated sport, emotional support from your social circle is not something baked into the culture (especially amongst older generations). Cishet male culture is particularly terrible at offering men the tools to talk through emotions and internalized discussions because it’s not something taught to them. It creates a culture of isolation which makes it difficult for bladers to reach out to their friends for support, which creates further self-isolation. That’s also a common thread with those struggling with addiction and recovery.

How does this form of seclusion play a part in substance abuse?

Isolation and addiction go hand in hand. The opposite of addiction is not sobriety, it’s connection. I feel our society is making great strides in helping the ‘macho man’ mentality die, and letting men finally feel more comfortable with becoming vulnerable and sharing their feelings.

It’s funny because one of the strongest things you can do as a human being is showing vulnerable with another person, yet it has been viewed as a weakness for so long. This is not something to go at alone. We need help and we need support. All anyone wants is to feel loved. To feel like someone actually gives a shit about you. By isolating [those who are struggling] this can never be achieved. We need connection.

How did you experience this isolation? What was the turning point in your road to sobriety?

I was living a very, very isolated existence. I worked a night job with one of my best friends who is no longer with us due to an OD (RIP Jesse, love and miss you, man.) He and I used drugs together, which was the extent of my social interaction. I would work through the night with almost zero human interaction and sleep during the day, all the while supporting a heavy heroin and benzo habit. At this point in my life, I hadn’t been skating for years.

My “A-HA” moment came one night shortly after getting to work. My job was going to grocery stores and de-icing the freezers. Before starting my shift, I was sitting in a King Soopers [supermarket] bathroom loading up a shot of heroin, when I had a thought. A very simple, but strong thought.

“If I OD’d right now, I would die in a King Soopers bathroom.” I had OD’d in the past with no change in my behavior, yet for some reason right then and there I knew, I fucking knew! Without a shadow of a doubt [in that moment], I was done. I wanted help. I wanted to end this cycle. I was going to do whatever it took to get sober.

That’s why answering the question, “Why can’t some people get sober?” is so hard to answer. It has to be a personal choice. The eureka is different for each individual.

Nothing greatly significant had taken place. I had lost fingers…didn’t get sober. I had been homeless… didn’t get sober. I had OD’d… didn’t get sober. Yet here I was with a stable job, roof over my head, no significant event taking place, and I had this moment of clarity.

I picked up my phone and called Parker Valley Hope, a rehab center I had been to a few times before and asked for a bed. A few days later without notice I told my parents I was checking myself back into rehab for the sixth time.

I had a plan, though. I wasn’t just going to check myself in, complete the 30 days and go off on my own again. I was lucky enough to be assigned a counselor I had been assigned to the previous time I was there, Robert Joslin. On my second day there when I was able to meet with Robert, I ran to his office and told him, “send me somewhere long-term!” Parker Valley Hope was only a three-week facility and three weeks wasn’t going to cut it for me. There was a newer treatment center in Colorado Springs by the name of Triple Peaks Recovery Center, a six-month intensive treatment program. Robert told me he was transferring there in a few weeks and that if I chose to go there, he would put me on his caseload.

I didn’t ask a single question. I said, “Yes, sir. Send me now.” Without completing the three weeks at PVH, I was picked up a few days later and sent to Colorado Springs. Without going too deep into the details, I did every single thing (and more so) I was told to during those six months. Counseling groups twice a day for the first few weeks, followed by counseling groups once a day for the remainder of the six months. An AA meeting every single day, sometimes two to three in a day. I got a sponsor. I worked the twelve steps. My life DRASTICALLY changed.

Above all else, I made connections, friends, and brothers in recovery all coming together for the same purpose — to become the best versions of ourselves we could be.

For those struggling with sobriety and addiction, what advice would you offer them?

The best advice I can give is to ask for help and don’t be scared to ask for help. You do not have to do this alone. It’s going to be hard, it’s going to be scary, and it’s going to be uncomfortable, but can it really be any worse than what you are already going through?

You need to get comfortable being uncomfortable. That’s how we as humans grow and learn. You are leaving behind the things that bring you comfort and familiarity. You need to learn new coping skills to deal with the underlying issues of why you use drugs and alcohol. Putting substances down isn’t enough. There’s work to be done and you need to be willing to do whatever the hell it takes to achieve that.

Most of us abused drugs and alcohol for a long time, so do not expect it to be a quick process. It’s going to take time. It’s okay to struggle. Relapses happen, but take it as a learning experience as to what to do differently next time. Don’t be too hard on yourself. This will be the hardest thing you have ever done in your life, but it will also be the most rewarding.

Someone asked me early in my recovery, “what do you want your life to look like in the future?” Before I could answer, they stopped me and said, “whatever you’re imagining doesn’t even come close to what you are capable of.” They were right! I would have cut myself way short of what I had accomplished in the past seven-and-a-half-years of my sobriety.

A repeated theme throughout our talk on the phone was chasing a dopamine high. Whether it be from skating a new spot, getting noticed for our skating, stronger drugs, building a business from the ground up and improving it each day, finding challenges in your new hobby, golfing. There is a constant motivation to find novel experiences.

Can you walk us through how addiction fits into this for you? What kind of challenges has it presented?

It’s important to understand that our brains need to be stimulated and challenged, especially as a recovering addict my mind can run rampant. Skating is a great way to stimulate your creativity. As a recovering addict, it gives me something to throw my addictive behavior into towards a positive outcome.

For myself, it’s a sense of discipline. You don’t have a coach on the sidelines telling you what to do unless you have Ian Walker behind the camera or Scott Olsen critiquing your clip. They’re two dudes within the skating community I’m incredibly grateful for. They helped push me to become the best skater I could be.

It’s the same when you’re in recovery. Having to build your network and connections, you need others to help hold you accountable and keep pushing you through the tough times. It’s a way to create something the way you want it. It’s a way to work through fear and overcome it.

There’s no better feeling than standing over a spot, absolutely terrified to attempt a trick then getting the clip and accomplishing exactly what you came there to do. It helps keep me present and in the moment. All of your focus is on that one trick. Almost like a fucked up form of meditation. I’m the worst when it comes to just chilling or relaxing. I still deal with a tremendous amount of stress and anxiety, yet skating helps clear my mind and focus on something else for that moment. I need to stay motivated, active, or working towards a goal. Otherwise, I risk falling back into old behaviors.

I skated harder than I ever have during the filming of Crazy Pills, a video by Ian Walker. If you haven’t seen it, you can watch the full video on YouTube. During that process, I found a deep sense of accomplishment. It was the second full part I had ever filmed and first full part in a full-length video. Lots of failures, but even more triumphs. I’m incredibly proud of how it came out!

None of that would have been possible without perseverance or walking through fear. Motivation to put together something I would be proud of wouldn’t have come without determination, discipline, and the help from my community.

Most of the filming took place during the summer of 2020 at the height of Covid. I had previously been working as bartender and with the shutdown of bars/restaurants, I was out of a job, living on unemployment, and could just enjoy focusing on skating. This was great for that period of time, but my wife (then fiancé) noticed I wasn’t continuing to stay motivated in other avenues of my life. She was the one who helped push me towards something better (Love you, Mara.)

Notice a trend here? Connection, support, community.

I started thinking about what I would do for work. I’m a high school and college dropout with no career. I had worked for a handful of treatment facilities throughout my sobriety with a few other random jobs in between. I always had the dream of opening my own treatment facility, but I had no real plan in place. Goals and dreams are great, yet without a plan of action they mean nothing. I directed myself and got to work. I started by googling “how to create a business plan”, did a ton of research, watched a ton of YouTube videos, and began building a plan of action. I worked tirelessly to make my dream a reality.

In this way, my addiction adds value to my life by obsessing over whatever I’m working on. When I make a choice to do something, I do it with passion.

I opened my first recovery home in February of 2021 with my business partner Matthew Trenk. He is the most genuine person I have ever met. Over the past year and a half, we have gone from one to three recovery homes, as well as created an incredible recovery program to help men suffering from addiction. It is our goal at Sophrosyne Sober Living to provide an all-pathways recovery home with a safe and structured living environment to help individuals recover. We provide resources that best fit each person’s needs. We are continuing to grow and becoming the best program we can be.

I picked up golf in May 2021 after suffering a knee and ankle injury that put me out of skating for the rest of the summer. Like with skating, golf gave me a sense of discipline. It helped with patience and expectation management. I can obsess over golf rather than drugs or alcohol. It’s something new to stimulate my brain and progress. It helps keep me motivated and driven.

I’ve started skating again more recently and while I don’t think I’ll ever skate at the level I was at a few years ago, the passion I have for skating is still there.

There’s a quote I would like to end on:

The quality of people around you dictate the quality of your life.

If there’s one thing I would tell anyone, it’s build connection.

YOU CAN FOLLOW KYLE VANDONGEN ON

INSTAGRAM @KYLEVDOG

FACEBOOK

WATCH CRAZY PILLS ON YOUTUBE

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON SOPHROSYNE SOBER LIVING,

VISIT SOPHROSYNESOBERLIVING.COM

@SOPHROSYNESOBERLIVING